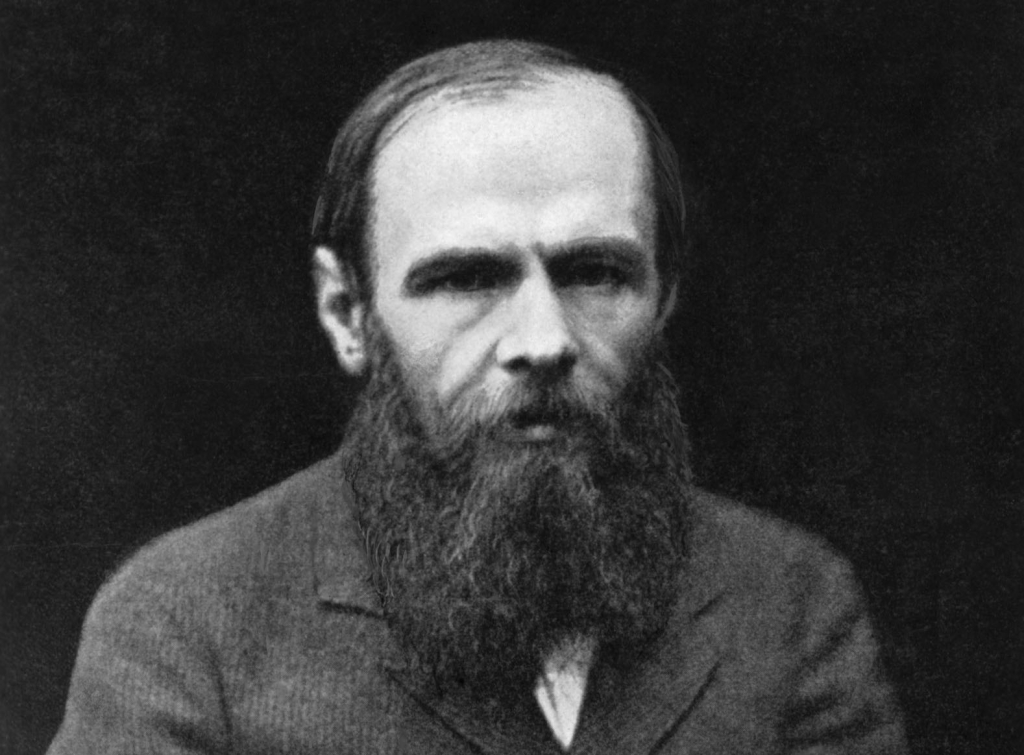

Today is Fyodor Dostoevsky’s birthday.

Dostoevsky is my favorite dead Russian. I even think he could have taught Tolstoy a thing or two about character development. I find myself connecting and relating more with his characters, than Tolstoy’s. With Tolstoy, I find myself asking “Why do all your characters seem so whiny and their dialogue so long?” With Dostoevsky, I respond more like “Yes–tell me more about this protagonist! and “Golly day, I would have said or reacted in the very same way!”

Dostoevsky is my favorite, 198 year old, dead Russian author.

There is great value in reading classics by authors who are no longer in this world. C.S. Lewis said this about reading old books, in his own book, “God in the Dock”:

Lewis was mostly referring to non-fiction works with an emphasis on theology. But I believe the sentiment is true about works of fiction as well. His reasoning is this:

The classics are called classics because of this exact truth that Lewis alludes to here: they have been tested against thought down through the ages. Maybe not Christian thought in all cases, but a great deal of them have that in common. Their hidden implications have been brought to light through time, careful analysis and thoughtful discourse. They remain on reading lists today precisely because they are, well, classic.

I first encountered Dostoevsky’s writings through Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov. I’ve gone on to read The Idiot and Notes from the Underground.

What drew me most to his writings, is that Dostoevsky understood the fallen nature of man. He also understood the magnitude of grace. J.I. Packer captured it here, in contribution to the book, “The Gospel in Dostoevsky”:

Dostoevsky had a philosophical bent to his writings, and married this theme to commentary on the nature of sin and man and the nature of God, through the way his characters reacted to the world around them–as well as how they reacted to their own minds and souls.

As such, I think that what sets Dostoevsky apart from Tolstoy and others of his contemporaries, was “felt thought”.

He was an ideological novelist; the ideas that his characters had–even the very thoughts they thought–became a part of who they were. And all of it was so masterly woven together, that, if you’ve read the book, you can’t help but picture a character from his books, without also instantly sensing some of the major thoughts and ideas that shaped who that character was. For instance, when I think of Raskolnikov, from Crime and Punishment, my mind instantly conjures up a dichotomy of ideas, thoughts, and feelings about him—anti-social, a bit of a psychopath, but infused with compassion and warmth at the same time. In fact, I can describe, in a sense, the thoughts in Raskolnikov’s mind far better than I can describe the events in the book, or even what he was depicted as looking like—because it is the thoughts and ideas that resonated with me, while the story itself became background. It was “felt thought.”

One of Dostoevsky’s closest friends, Nikolai Strakhov, described his friend like this:

The most routine abstract thought very often struck him [Dostoevsky] with an uncommon force and would stir him up remarkably. . . . A simple idea, sometimes very familiar and commonplace, would suddenly set him aflame and reveal itself to him in all its significance. He, so to speak, felt thought with unusual liveliness.

I wish I possessed more of that characteristic of “felt thought”, in my journey as a Christ-follower.

Too often I approach the things of God with a detached viewpoint. I want to analyze it. I want to quantify the mysteries of God into neat little sets of data that I can easily digest and categorize. I don’t want to feel thoughts about God. I want to think about God—I like thinking about God. Very much so. But when it comes to feeling those thoughts; that’s when I tend to run.

I think that is natural, though, to some degree. Feeling deeply about anything–God, family, abortion, slavery, evangelism, even our dog–feeling deeply can hurt. It can be painful. And, even the very good things–even joy–can be painful, sometimes. And who runs to embrace such pain?

But, pain at times, is necessary. I am currently recovering from surgery. It hurts. But that hurt is a result of necessary correction, in my body.

The same goes for the things of God. It hurts, to think of His sacrifice, for us, on the cross. It hurts, sometimes, to think of His mercy, and even more so, our need for His mercy. It hurts, to look Him in the eyes.

I know this, full well.

And yet, sometimes that is exactly what is needed. Sometimes we need to “feel thought”, and experience our God in the same way the woman did in Luke 7: the “sinner”, who washed Jesus feet with her tears, as she felt the painful weight of who she was….and, the joyful weight of who Jesus was.

It is easy to run away from God. To study God, as opposed to worshiping God. To analyze, rather than feel the magnitude of His Grace and Mercy.

But here’s the thing. Just like Dostoevsky and his characters displayed such rich, encompassing passion through their felt thoughts, I too, want to strive for that in my relationship with my Savior and my recognition of what He has done for me, through the cross.

I want my passion to be authentic, whether in joy or in pain. Just like Raskolnikov, in Crime and Punishment.

Authenticity comes from allowing “felt thought” a place in worship.

SOOOOO glad to hear from you again! I’ve missed you. Welcome back and I hope we all hear from you often!

Thank you friend! It is good to be back; ready for life to slow down a bit!

Ok, so Larry posted a picture of you both on FB today – you are both running – can I just say that I SO LOVE THAT PICTURE! <3

And, I love you! 🙂

S